- I Have a Ribcage; You Have a Ribcage

- Posts

- The Aloneness of Love

The Aloneness of Love

James Baldwin and falling head over heels at the end of the world

The headlines these last months have hardly felt loving. But I fell in love nonetheless.

We’ve joked that in our socialist feminist utopia, we should be granted a lesbian falling-in-love sabbatical. The montage would go like this: We made some weird gay music/experimental performance together. She made me a Dutch baby with pistachio sugar. I made her molten chocolate cake—a perfect ‘90s trend dessert that, in my opinion, is the height of romance (this will probably gross you out, but she fed it to me with a tiny silver spoon!). We read essays to each other out loud in bed in the evenings: I read her this one, on the pleasures of eating in bed (I love to; she hates to); she read me this one, on lesbian literature and the mommy-baby/serf-tyrant framework. She reads me poems (I felt/our gap/about to/be closed). We’re trying to watch the whole Nora Ephron canon.

We begrudgingly do our jobs in between.

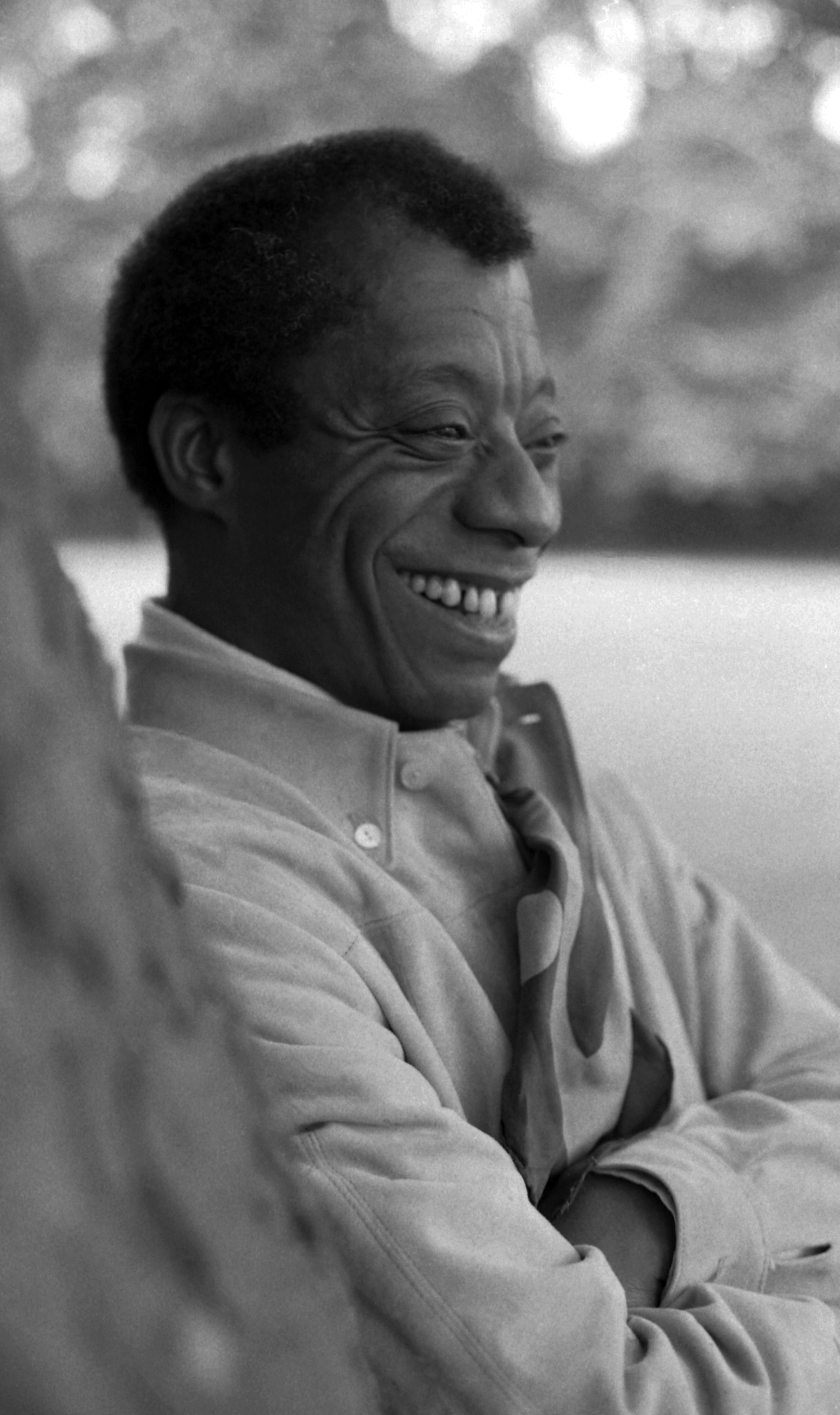

One of my jobs involves tutoring standardized test curricula to overachieving children. This part of my job is sterile, and it sucks. But one particular lesson asked a student to think about composition. So, as an example, I trotted out James Baldwin (as I often do; he’s an education, after all).

In his essay “The Creative Process,” Baldwin writes, “Perhaps the primary distinction of the artist is that he must actively cultivate that state which most men, necessarily, must avoid; the state of being alone.”

This is a quote that my cruelest parts take up as a weapon—an indictment of my mediocrity, or silly chattiness, or wasted time. I am going to die, and I will not have made the great work of art, they taunt. At their worst, they’ll take a swing at María, blaming all the afternoons we’ve spent staring at each other for my “idleness” and blank pages.

But my cruelty loves a facile reading. Baldwin is not calling for asceticism, individualism, dogged productivity, and self-flagellation until more and more and more art is cranked out. No, he is calling—as he so often does—for love:

The state of being alone is not meant to bring to mind merely a rustic musing beside some silver lake. The aloneness of which I speak is much more like the aloneness of birth or death. It is like the fearless alone that one sees in the eyes of someone who is suffering, whom we cannot help. Or it is like the aloneness of love, the force and mystery that so many have extolled and so many have cursed, but which no one has ever understood or ever really been able to control.

I have felt, on this page, on the phone with hurting friends, in prayer, in this sweet new girlfriend’s arms, this aloneness. It hurts like hell, but there’s sturdiness, or exhaltation, or…me if I dare go there. “If you can’t love anybody, you’re dangerous,” Baldwin says in an interview. “You have no way of learning humility, no way of learning that other people suffer, no way of using your suffering—and theirs—to get from one place to another.”

Today, on the train, while hearing my inner monologue chant I hate myself, I prayed to the divine. She replied: I love you whether you want me to or not. What an excruciating response; I am so grateful.

To fall in love like this forces a confrontation with the self—a lonely process, paradoxically. As Baldwin says, it has a “force and mystery” that cannot be controlled. María has a vulnerability that demands the same from me, which can’t be half-assed. “No man and no woman is precisely who they think they are,” Baldwin said. “Love is where you find it. You don’t know where it will carry you. And it is a terrifying thing, love.”

“The aloneness of love,” according to Baldwin, is the antidote to a society that demands dishonesty and dissociation. He writes:

The entire purpose of society is to create a bulwark against the inner and the outer chaos, in order to make life bearable and to keep the human race alive…A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven. One cannot possibly build a school, teach a child, or drive a car without taking some things for granted.

The everyday mechanics of living in our society are not loving, and they are not honest. In his essay “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide,” Fargo Nissim Tbakhi calls them the dailiness: “oppression so pervasive as to form an atmosphere we move through…the structural and therefore constant violence that forms the machinery of genocide and greases its wheels.” I’m helping kids write college essays wherein they imagine bright futures studying biochem, devoid of climate collapse and concentration camps. I pay my rent every month like a good girl. I write marketing copy while wildfires pillage, submit my quarterly estimated taxes while the bombs they fund fall. I even catch myself meandering into top-of-the-escalator, “stable,” picket-fence romantic fantasies; in reactionary times, in the headiness of new love, it’s tempting to betray the family-abolitionist, anti-property queerness I aspire to.

Instead, Baldwin writes, “The artist cannot and must not take anything for granted, but must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.”

Baldwin ends the essay by zooming out to the impact of the artist on the nation and history:

[The dangers of being an American Artist] rest on the fact that in order to conquer this continent, the particular aloneness of which I speak—the aloneness in which one discovers that life is tragic, and therefore unutterably beautiful—could not be permitted.

A paraphrase for this could be Dr. Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s “Where life is precious, life is precious.” If one really surrenders to the aloneness of love, one cannot look away from our empire’s several-hundred-year-long disregard for life. So it’s easier, for many of us, much of the time, to pay rent or study for the SAT or dream of nice furniture. But “the dailiness” is spiritually poisonous—my life becomes less precious the more I grease its wheels. Each moment I numb or avoid the aloneness, this too-short life slips by.

One night, in the early, giddy, entwined days of love, when our arms were always crossing the edges of each other’s bodies, I felt afraid, enmeshed. Suddenly, wrenching myself from the depths of her eyes, I said, “I’m feeling avoidant.” She recoiled, abandonment fears rearing up. We were now in a little bit of a conflict—one of our first. “I don’t need you to comfort me,” she said. I desperately wanted to comfort her; I desperately wanted to run far away.

“Can I read something to you?” I asked. I wanted a way to stay connected without “processing” or further enmeshing. “Sure,” she said, unconvinced but willing.

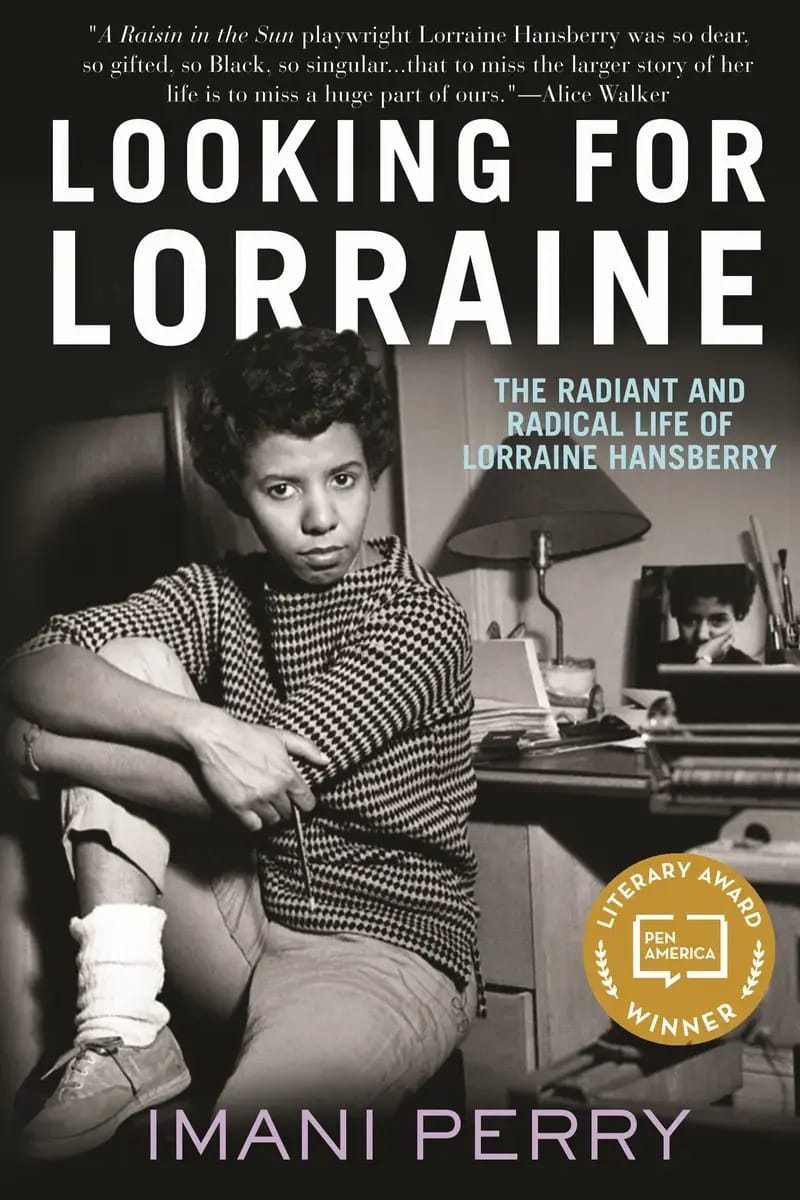

I rifled through the internet for some of my favorite writing and started looking for an excerpt from Imani Perry’s “third-person memoir” Looking for Lorraine. At first, I wanted the chapter about Lorraine Hansberry’s lesbianism (did you know that she and Mary Oliver shared a lover?! No! Not at the same time, if that’s what you were thinking! Decades apart!). But I ended up finding the chapter about her friendship with Baldwin. She called him Jimmy. They danced together, like in this magical photograph. He called her “Sweet Lorraine”. After her death—at 34, my age—Baldwin wrote:

Her going did not so much make me lonely as make me realize how lonely we were. We had that respect for each other which is perhaps only felt by people on the same side of the barricades, listening to the accumulating hooves of horses and the heads of tanks.

Not enough plays take place in bedrooms (American theatre has too much family drama, not enough sex), but I always relish the stage pictures anchored to a bed. My back faced her, sitting on the left side; her back faced mine, curled up on the right side. She cried at the beauty of Perry’s prose, at the power of these artists’ minds. I cried about the too-early loss of Lorraine, how much Jimmy loved her, the fierceness of her politics (and how much we need them these days, amidst the horses and tanks). We both cried at the terror of falling in love. The terror of falling in love now, when the world, as we know it, is falling apart. It is lonely beyond belief, but we gotta be lonely together.

I think of Lorraine many nights, remembering that she was laid to rest at about my age, pausing not to take for granted these days, this time to make art, to fall in love, to enjoy this lesbian ease I’ve slid into—something she prefigured but never experienced openly. I think of her creative love affair with Jimmy. “That marvelous laugh. That marvelous face. I loved her, she was my sister and my comrade,” he wrote.

A mantra of the last year has been Tbakhi’s: “Like a net, we tie ourselves to one another to stop the dailiness from getting through,” he writes. “We tie ourselves tight enough so none of us get lost along the way. Maximal commitment, minimal loneliness, to paraphrase a comrade.” Sisters, comrades, lovers, neighbors, strangers, friends (since pre-school, since middle school, since yesterday), things are bad and about to get much worse; lash yourself to me and to one another. We must learn to be alone; may we be less lonely. We might be lonely; we’re never alone.

Gratitude to Ro White, Courtney Smith, Alexis Lopez, Martha Hurwitz, and Raechel Anne Jolie for their feedback and edits on this essay.

Think someone would enjoy this newsletter? Forward it along!