- I Have a Ribcage; You Have a Ribcage

- Posts

- My Favorite Art of 2025

My Favorite Art of 2025

Three mini-reviews and a lighting round

Since beginning this newsletter and since my algorithm started feeding me “journal ecosystem” videos (It’s overconsumption! It’s perfectionism porn! But I love writing things down on beautiful paper with beautiful pens!), I’ve started keeping a notebook dedicated to the art that I consume. For each book or play or film, I jot down a few things to help me remember what it was and what stuck out to me.

When I was about to graduate from college and was freaking out about building a life in the theatre, a mentor suggested I see one play each week. Chicago is a rich enough theatre town that this wasn’t a hard prescription to fill. I’ve returned to something like advice over the years in moments when I’ve felt creatively stuck: see some art each week.

With these practices in mind, this year, I saw a lot of art! I had one of my best reading years ever (especially memoirs and fiction), I saw a lot of dance and experimental performance, and I saw some excellent documentaries (a medium I’m feeling increasingly called to). Below are some of my favorites, in the form of three mini-reviews and then a “lighting round” of runner-ups. Happy New Year and may 2026 be full of great art!

Manual Cinema’s The 4th Witch

Manual Cinema created an art form: They use a mixture of human silhouettes and overhead projector shadow puppets (yes, like from 8th-grade algebra) to create silent films. I’m going to do that insufferable hipster “I liked them before they were cool” thing here, but I’ve loved Manual Cinema since I first saw their Ada/Ava in a second-floor, twenty-seat performance space in Chicago. This year, I saw them sell out the several-thousand-seat Moore Theatre. If they’re touring to your city, don’t miss them.

Their most recent work, The 4th Witch, is a sideways take on Macbeth, featuring a young girl orphaned by Macbeth’s wars. The visuals are stark and dramatic, using just black, red, and white, and remixing Macbeth’s key symbols (the dagger, the cauldron, the bloody hands). Its live score (composed by Kyle Vegter and Ben Kauffman) features three women: a violinist (Lucy Little), a cellist (Lia Kohl), and a pianist (Alicia Walter), all also vocalists. They sing in spooky harmonies and erupt into cackles, sounding gorgeously like witches.

The story is set in France during World War I, but as planes fly overhead and bombs fall on buildings, I immediately thought of Gaza and children orphaned, parents trapped under the rubble. I don’t know if this was intentional on Manual Cinema’s part or not. But as the work finished, I pray that the children of Gaza get the ending of our 4th witch: magical powers, vanquished warlords, a return to the cafe their parents owned, plentiful good food.

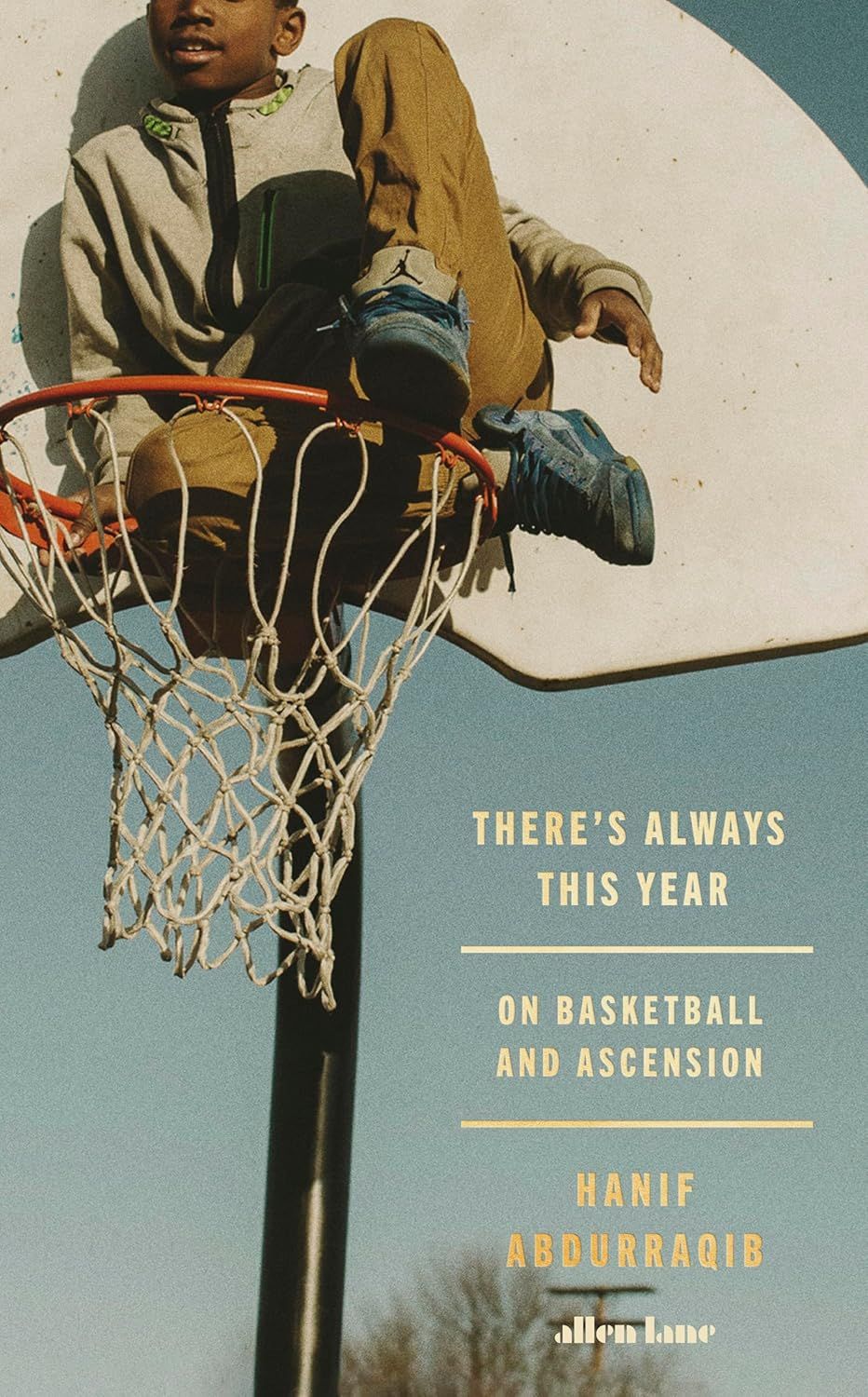

There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension by Hanif Abdurraqib

I really don’t care about basketball, but I adored this book about it.

There’s Always This Year is a memoir about place—Ohio in particular—told through Basketball. It has a high-concept format: the book is organised like a Basketball game, beginning with the pregame, then the first quarter. Each section break is a moment on the timer (10:27, 9:30, 0:00). “Intermissions” and “timeouts” are opportunities for formal experiments: film reviews and poems.

Abdurraqib’s prose reads like scripture, which, if we were writing about experimental film or Shakespeare, might be so pretentious I’d wanna put my fingers down my throat. But the sacred/profane contrast of revering basketball with divine attention feels both playful and sincere. Of “The Decision,” LeBron James’ choice to leave the Cleveland Cavaliers, Abdurraqib writes

Tell me you haven’t invented a reason to transform the beloved into the wretched, at least one time, to yourself, in the quiet of a dark room, when the weight of loneliness demanded you find a target, at least for now, at the start of it all.

It is a book for artists and neighbors, fathers and sons, sports fans and agnostics, but also for organizers. In the acknowledgments, he thanks “the organizers in Columbus, who help bridge the gap between the city as its false self and the city as its true(r) self. An honor to be a witness to, and participant in, your work.”

Sugarcane directed by Julian Brave NoiseCat and Emily Kassie

In an early scene in Sugarcane, Charlene Belleau, a residential school survivor and lifelong activist investigating the St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School, beckons Julian Brave NoiseCat, one of the filmmakers, to the school’s barn. Charlene begins a ceremony over him. “Our elders are now looking to you to listen to our stories,” she says. “You’re bearing witness to a time in history when our people are gonna stand up. You’re gonna make sure they’re held accountable for everything they’ve done to us.” When this scene was shot, Julian was not yet one of the subjects of the film; he was one of the filmmakers behind the camera. In an interview, Co-director Emily Kassie said that Charlene had texted her that day to take Julian to the barn and bring her cameras. ”It was as if the world broke open,” Kassie said. Belleau seemed to know that Julian’s story was essential. She was right.

The making of this film is full of haunting coincidences. I saw the film at Seattle International Film Festival with a talkback from NoiseCat. He told the story of how the film came to be: After unmarked graves were found at a residential school in Kamloops, BC, in 2021, Emily Kassie—a human rights reporter/documentarian and an old friend from a journalism job—called him asking if he wanted to collaborate on a film about investigations of residential schools. He said he wanted to take a little while to think about it. In the meantime, Kassie started cold emailing Indigenous communities across Canada, asking them if they’d be interested in having their investigations documented. The very same afternoon, Willy Sellars, the chief of the Williams Lake First Nation, called her back. “The creator has always had great timing,” he said. Just the previous day, in a meeting about their investigation, they had said that they should have someone document it.

A few weeks later, Julian called Emily back, saying he was in. When she told him about her call with Chief Willy Sellars, Julian said that he paused for a long time. “Did you know that that was the school where my family was taken and where my father was born,” he said. Of the 139 residential schools across Canada, she chose this one. Ultimately, Julian’s father was the only survivor of one of the school’s most horrifying atrocities; there was a crucial truth for their line to find through this investigation and this film. It was meant to be.

In his talkback at SIFF, NoiseCat said that, through making this film, “I healed my relationship with my dad”—a statement few get to say so definitively! This film radiates with care and trust; how else could it so tenderly share the stories, traumas, and healing of its subjects? It is beautifully and wonderfully made, guided by its makers’ integrity and their connection to something much greater.

Learn more: An interview on the LANDBACK for the People Podcast.

Runners Up

Girl Dinner, created and performed by Kelly Langeslay, BASE Experimental Arts: A piece of dance-theatre autotheory about queer performance, suicide, Barbies, and cake. Some favorite moments: Langeslay pulling quotes of queer theory from their pocket and eating them after reading; a devastating sequence of casting themselves off a windowsill and sticking their head under the sink, on repeat; asking the audience to clean up the stage (covered in cake and water) while they dressed an audience member in a prom dress in the bathroom.

Indian School, created and performed by Timothy White Eagle, On The Boards: Could be a companion piece to Sugarcane, about residential schools and fathers and sons. Extraordinary theatricality and intimate ritual. Beautiful projection design. It was smartly staged in traverse, physicalizing the river that is central to the story. White Eagle’s energy is incredibly grounded, breaking down any barrier between audience and performer, rendering us all present in the same room together, available for the transformation he offers.

Emergence, choreographed by Crystal Pite, Pacific Northwest Ballet: a staging of a hive mind and interdependence featuring 48 ballerinas.

Severed, directed by Jen Marlowe, produced by Mohamad Saleh and Mohammed Mhawish: A short documentary following the life of Mohamad Saleh, a young man from Gaza who was shot in the leg by an Israeli sniper during the Great March of Return, and has been struggling to receive medical care since. From Donkeysaddle Projects, which creates documentaries and theatre while providing direct support to families on the ground, the film beams with the deep relationships that created it. The whole film is available on YouTube.

Dads by Drama Tops, Velocity Dance: Nightlife dance-theatre duo Elby Brosch and Shane Donohue’s evening-length work about dads and daddies. Highlights: The opening scenic design which made the whole room look like fly paper, but when the two performers leapt into it, the whole set collapsed to the ground around them; a moment when Brosch spoke tenderly about losing his dad at a young age while Donohue’s stood on a tire on his chest (“A bit too heavy,” Brosch would say in moments); the final scenic design, a stage-sized inflatable bouncy castle.

Godspeed You! Black Emperor, in concert: I’m a new fan of this band of French-Canadian anarchists that’s been around since the nineties. Swelling, trance-like music featuring a dozen instruments and black-and white film projections—of rural landscapes, of rubble, of oil refineries, of stock market tickers, of wildfires, of protestors in the streets. Read more: Martha Bayne’s essay on seeing them perform in a graveyard on the 10th anniversary of her father’s death; “Can there be a Guernica for Gaza,” Christopher J. Lee’s Jacobin review of their most recent album NO TITLE AS OF 13 FEBRUARY 2024 28,340 DEAD.

Think someone would enjoy this newsletter? Forward it along!