- I Have a Ribcage; You Have a Ribcage

- Posts

- "Cultural, Artistic Intifada"

"Cultural, Artistic Intifada"

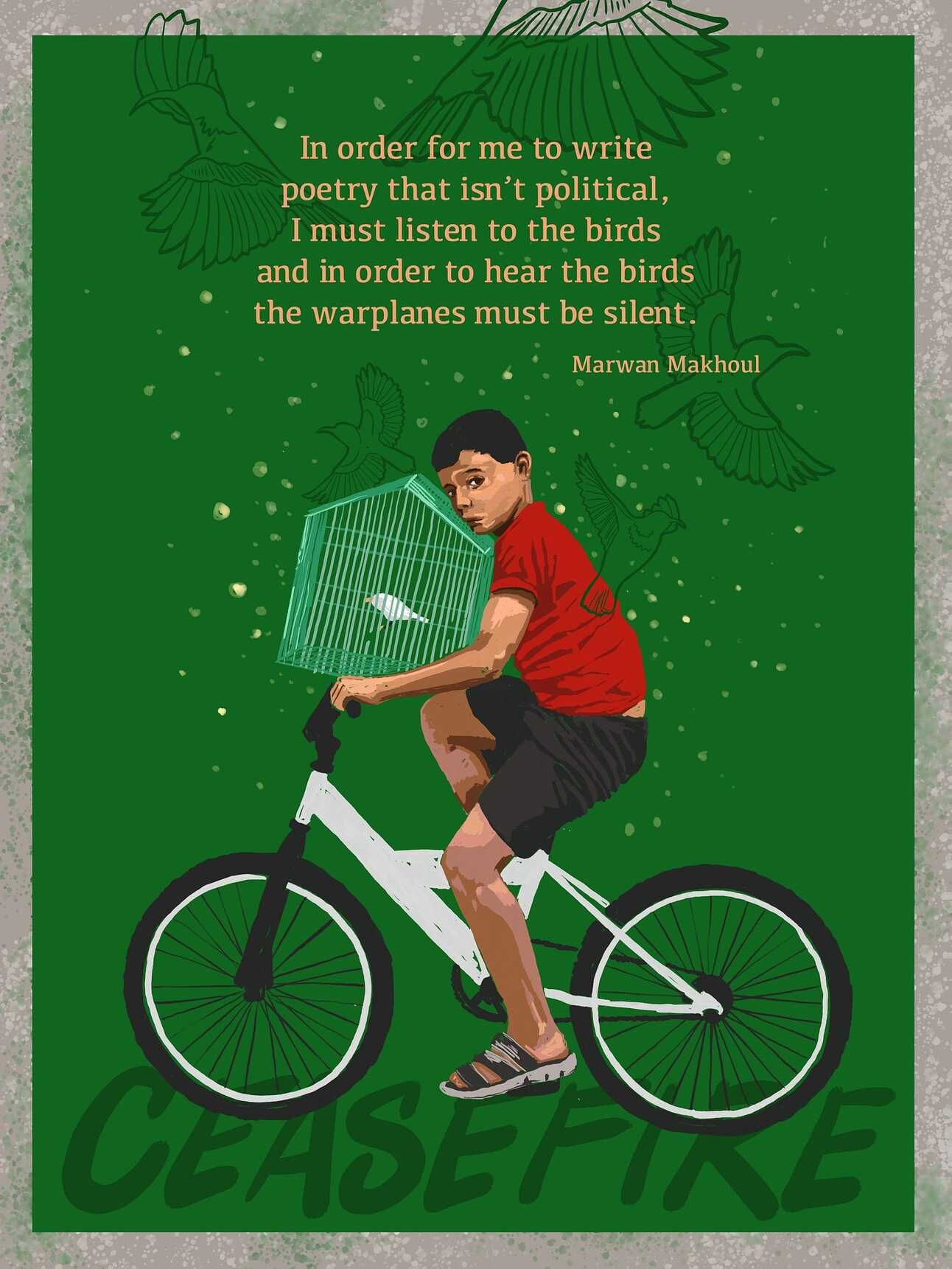

Inspirations and Calls for Artmaking in Solidarity with Palestine

When I was working at a theatre that sucked, I spent a lot of time, energy, self-deception, and lofty language defending the importance of the arts. When the art you’re making serves the status quo, you have to try really hard to prove it’s transformational. Politicization has offered me clarity; either the work matters or it doesn’t. I fight with myself a lot less. I want to make and see the shit that counts.

The Palestinian people are showing us that art really matters. The IDF is going after artists because they are dangerous to empire. Just in the last several weeks, the Israeli government assassinated the poet and professor Refaat Alareer; kidnapped poet Mosab Abu Toha; and raided the Freedom Theatre in the West Bank, kidnapping and torturing its leadership for more than 24 hours. These are just three of the most publicized examples; Lithub has aggregated a list of all the poets and writers murdered in Gaza so far in this genocide.

Today, I offer a curation of writings and videos about art and Palestinian liberation. In the Democracy Now piece I cite below, Freedom Theatre Artistic Director Ahmed Tobasi quotes Juliano Mer-Khamis, (one of the founders of the theatre) who called for a cultural and artistic Intifada. “I am asking all the artists in this world…”, Tobasi says, “We’re asking also all the friends all around the world, you have to unite, and we have to fight not just for Palestinians. We have to fight this planet, for humanity, for each community, and each country still under colonization or under occupation.”

As artists, we must make work that is dangerous to empire and nourishing to each other. Inspired by these thinkers, I believe with a newfound clarity that artmaking is crucial to the future of our planet. Let’s heed their calls.

Mohammed el Kurd, “On Mournable Victims”

A eulogy for Refaat Alareer:

If I decorate this euology with the kind of shiny adjectives we only gift our friends after they have died, I would be doing us all a disservice. After all, this was a man who loved to cuss and joke. Even when the bombs dropped he gave us laughter, and perhaps—indulge me—especially when the bombs dropped, he gave us laughter. So I’m not going to indulge in meaningless good taste because he gave us laughter, thunderous laughter, when the world ordered us to shrink and whisper.

Ahmed Tobasi, “Israel Raids Freedom Theatre in Jenin Refugee Camp; Director Speaks Out After Being Jailed & Beaten,” Democracy Now. (h/t )

But even though we still, in the Freedom Theatre, is a cultural, artistic place, where we have children, young people, girls, boys, women to come here to practice, to find a place where they can express themselves, where they can imagine there is a better life, a better place in this world, where they can decide their future in different ways, to choose to be different from the reality that we’re living.

And still the Israelis come, and they’re telling us, “No, you cannot dream. You cannot think that you can be something different from the reality around you. You are under occupation, and that’s your destiny as a Palestinian, to grow up, to be born, to grow up and die under brutal, crazy, violent occupation,” that they don’t believe in anything, not in art. They arrest us as artists, as the people who do theater. They arrest — they destroy everything that shows there is culture, there is art, that we Palestinians, we are a normal people.

Refaat Alareer, “English Poetry Lecture 1: An Introduction to Poetry”

Of course, we always fall into this trap of saying, “She [Fadwa Tuqan] was arrested for just writing poetry!” We do this a lot, even us believers in literature … [we say], “Why would Israel arrest somebody or put someone under house arrest, she only wrote a poem?” So, we contradict ourselves sometimes; we believe in the power of literature changing lives as a means of resistance, as a means of fighting back, and then at the end of the day, we say, “She just wrote a poem!” We shouldn’t be saying that.

Moshe Dayan, an Israeli general, said that “the poems of Fadwa Tuqan were like facing 20 enemy fighters.” … And the same thing happened to Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour. She wrote poetry celebrating Palestinian struggle, encouraging Palestinians to resist, not to give up, to fight back. She was put under house arrest, she was sent to prison for years.

And therefore, I end here, with a very significant point: Don’t forget that Palestine was first and foremost occupied in Zionist literature and Zionist poetry … It took them years, over 50 years of thinking, of planning, all the politics, money and everything else. But literature played one of the most crucial roles here … Palestine in Zionist Jewish literature was presented to the Jewish people around the world … [as] a land without a people to a people without a land. Palestine flows with milk and honey. There’s no one there, so let’s go. … And there were people — there have always been people in Palestine. These are examples of how poetry can be a very significant part of life.

Kelly Hayes, “On Palestine, Poetry, and Remembrance”,

In movements, creative spirits can make artists of us all as we use our hands, our bodies, and our voices to tell the stories of loss, love, and solidarity that unite us. Whether by tying our words together into kite tails or speaking in unison, movement art is not an individualist display, but an invitation into art, into the act of storytelling, and into the creation of a different world. In moments of direct action, we have the potential to embody art and story – like children, full of persistence and hope, running with kites on a still, foggy day, with their minds full of poetry.