- I Have a Ribcage; You Have a Ribcage

- Posts

- Art I’ve Thought About on Ketamine (Part I)

Art I’ve Thought About on Ketamine (Part I)

Holland Andrews, Robert Morris, slowdanger

A thing that I love about myself: When taking drugs I hate, I think about wild art.

I lost the summer of 2023 to a frightening bout of chronic pain. It left me homebound, immobilized, and terrified it would never change. It started one night when I couldn’t or wouldn’t stop writing ‘till 4 am, my right arm twitching and getting ever more painful. It didn’t get better for eight weeks.

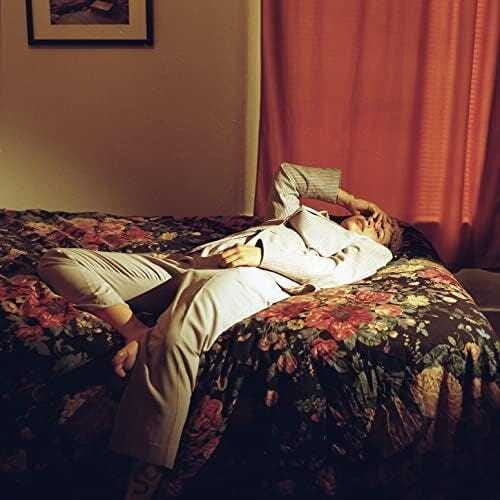

If a corporation wanted to steal your brain, their HQ would look like a ketamine clinic. (When I cracked this joke, someone joked back: “…but are our depressed brains really the ones they’d want to steal?” Another person kindly suggested that this might not be the “set and setting” I should choose for this experience. But I digress!). You sign up on a sleekly graphic-designed website. You enter a minimal waiting room with orchids on the end tables. You’re given excellent headphones, an eye mask, and soft (if soul-less) blankets. And then you do drugs and weep about your mom or your chronic pain or the escalating horrors of the world in a little room with a nurse practitioner you’ve never met. If they wanted to steal my brain by IV, this is how they’d do it.

I don’t really know why people do this shit for fun—I’ve hated it every time. At best it’s a bit above neutral and I babble about a “lesbian beach cave” or Barbie being God. At worst, I scream in terror or shudder or spend the day in bed with overwhelming nausea. But it really fucking helps: It breaks the spell—temporarily—of my aching fingers and shoulders and jaw. It’s a devil’s bargain, plunging me into an underworld in exchange for a taste of remission.

But every time, as I hallucinate, I think about incredible art—envisioning abstraction, science fiction, god, healing, a better world. What a subconscious I have! How avant-garde!

So here are a handful of micro reviews of art I’ve thought of in this altered state. For the most part, I’m not going to describe how I experienced these works of art on the drug. Listening to people describe psychedelic moments can be tedious (”I was one with the universe bro!”)—though at times, forgive me, I can’t resist. But in general, I will treat this as a frame, a prompt for sharing some stunning art with you.

Enjoy. Don’t throw up. Don’t let ‘em steal your brain.

Last fall, I saw Will Rawls’ performance piece [siccer], a work that “invites us to consider the ways in which Black bodies are relentlessly documented, distorted, and circulated in the media.” Rawls begins the performance in direct address, and names a list of movies that he devoured repeatedly during lockdown, including Daughters of the Dust, The Color Purple, and (crucially) The Muppets Take Manhattan.

The most transcendent part of the work was an uncanny performance of “It’s Not Easy Being Green,” from vocalist and electronic music composer Holland Andrews. Ever since, I’ve been obsessed. They’re a priestess.

Their album What Makes Vulnerability Good begins with the song “My Hands,” offering a direct blessing for my aching fingers, their synthesizers offering a gentle blessing.

I’m sorry that it hurts so much

I’m sorry that it hurts

I’m sorry that it hurts so much”

Take your hands out of your pockets

And put them in a warm place

Like my hands.

But the album then brings me into the pain. With “Tusk,” they let out a wail that feels ancient, rakes their vocal chords, calls out to a more forceful god. In an interview, they said “Grit is there. It’s to acknowledge the suffering and also to be told ‘I love you’ at the same time.”

Andrews identifies as a healer, and they have healed me. In their words,

You need to know where the wound is in order to heal it. I am offering this wound that I’m also trying to heal in real-time while performing or while I’m writing, knowing the shape of my wound may be different but it’s the same as everybody else’s. I’ve built up a lot of really masterful walls inside to keep myself protected, so when I can effectively break through them in order to allow what needs to come out so I can love more deeply, then I know it was a success. If it worked on me, then it can work on someone else!

I’m in my body enough these days—in sickness and in health—that I can feel art do its job: I can feel my masterful walls breaking down, I can feel the artist loving me through the hurt, I can feel them putting my aching hands in a warm place like their hands. They might not have known they’d collaborate with a medical dissociative potion, but what a spell.

They end the work with “Emotional Separation Meditation.” It sounds like the Milky Way. Their hums and soprano cradle me, landing me gently back to earth.

Holland: Thank you thank you thank you thank you.

In Seatac, there was an abandoned industrial gravel pit. But in 1979, King County commissioned “land artist” Robert Morris to create a 3.7-acre sculpture. Morris cleaned up the gravel pit, removed undergrowth, terraced it, and planted rye grass. The result is a massive, deep, swirling, grassy hole in the ground. It looks like the aftermath of a UFO.

I went with a friend almost a year ago and we stumbled down the impossibly steep slopes (pictures can’t quite capture how deep it is). When you lie on the ground at the bottom, you can’t see outside the basin.

As we lay at the bottom, murder after murder of crows flew overhead like they were modern dancers “activating” (to use a pretentious art word) the sculpture. They entered the frame, and then exited. Then another murder did the same, while I lay there immersed in the earth.

The industrial gravel pit doesn’t have to stay that way. The grass can be sculpture. The crows can perform.

slowdanger’s dance piece SUPERCELL

Anna Thompson begins SUPERCELL lying on the floor bungee-corded to a three-gallon plastic bag of water. They are also strapped to four other dancers, each attached to similar water rations. The quintet is interdependent; water is life.

But within a slow twenty-minute sequence, Thompson has amassed all six jugs of water and cut ties with their fellows. They literally tie themself in knots, wrapping themself in the many yards of abandoned bungee cords. They then hobble downstage, struggling under the weight of all their hoarded water. Later, they sing into synthesizers, “I could change, but I won’t.”

Using multimedia dance theatre, slowdanger has created an embodied allegory for the climate catastrophe: The Global North is hoarding and extracting resources, we’re ever more desensitized and sensationalized by media, and the only way forward is a radically different epistemology.

The piece has a fascinating bibliography, including some books I’ve read (The Fifth Season, How to Do Nothing, The Parable of the Sower) and some I’d like to (Hospicing Modernity, The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, and Joyful Militancy). I’m a dramaturg, so I love this.

I have some formal critiques of the piece: The language is often feels too literal (compared to the dance’s effective abstraction), there are one too many artistic gestures (I think I’d cut the live-streamed video), and both overlapping dialogue and direct address are overused tools. But It creates a dramaturgical, embodied sketch of our present moment in the Anthropocene. It haunts me—as I take these drugs, scroll the genocide, sit with trees, await the smoke.

Last fall, I began reading about the history of radical, lefty, anti-Zionist Jews, namely the Yiddish anarchists and the Labor Bund. In an interview in Jewish Currents, Anna Elena Torres says:

Yiddish anarchism was invented by refugees who theorized from their experience of border crossing—how does that history relate to anticolonial anarchisms and indigenous critiques of the state? I think both share a consciousness of deep time and life before the rise of a nation-state; this remembering has the potential to destabilize the present moment, reminding us that there’s nothing truly inevitable about militarism and nationalism.

The SUPERCELL bibliography includes “the time being”, a translation of Uji, the title of a nearly century-old text by Japanese Zen Master Eihei Dogen. “The time being is deep time, as opposed to linear, chronological time. The time being is a kind of eternal present.” Drawing from this, one of the ensemble’s “process terms” is “slow time”: “A state that we enter in the fall. A significant shift in perceiving time as extended and infinite. In a state of time that has existed long before us and will exist long after.”

SUPERCELL ends with an embodiment of this “deep time”: dancers moving glacially across a barely-lit stage, cloaked in giant pieces of fabric. In the dark, it invites me into the time of trees, or ancestors, or soil, or the womb.

This year, I’ve prayed, again and again, to deep time everywhere I can find it: God, show me it doesn’t have to be this way. God, help me tolerate destabilization. God, knowing what has existed long before and will exist long after, show me a way through.

Edit 9.30.24: When I originally published this, the subtitle of the piece was “It’s legal, I swear.” I meant it as a joke, but I pretty immediately regretted it because I don’t really care if people use it “illegally” and there are lots of barriers to using it how I did. Plus it makes me sound like a square!